General Anatomy

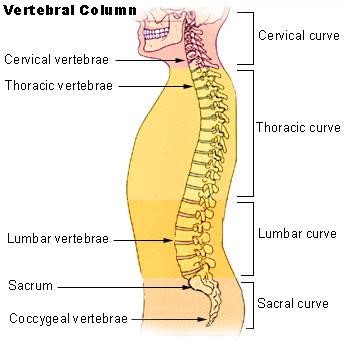

The Spinal Column is made up of four distinct areas:

-

Cervical (neck)

-

Thoracic (mid-back or spinal part of the rib cage)

-

Lumbar (low back)

-

Sacral (bottom).

Each part is made up of ‘motion segments’ that consist of bones called the Vertebra and the Intervertebral Discs.

Ligaments and muscles hold all these together.

Each part of the spine is curved; either leaning forwards called Kyphosis or leaning backwards called Lordosis.

This section explores each part of the spine.

Function of the Spine

The functions of the spine including protecting the spinal cord that is inside the canal and all the nerves.

It also provides stability and balance by supporting the neck and providing an upright position.

The spine moves in an intricate fashion to allow us to walk on two legs in a reciprocating manner as well as by providing attachment to muscles and the limbs.

The spinal column is also full of bone marrow where blood cells can be formed as well as a major storage point for numerous nutrients essential for life.

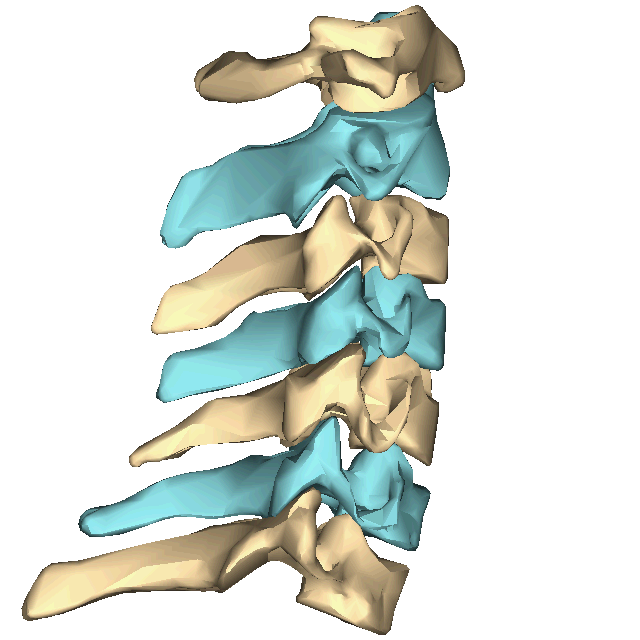

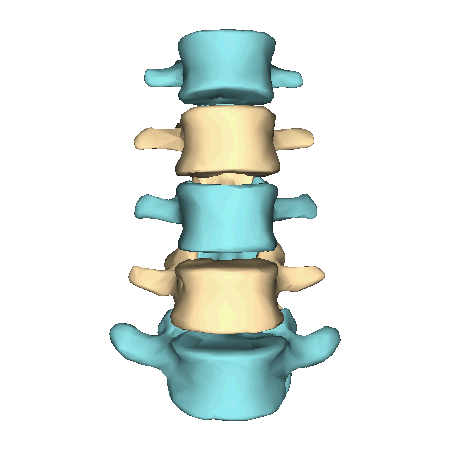

The Vertebra

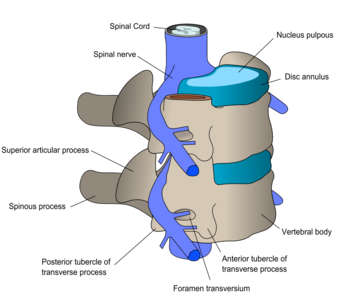

The vertebrae are the building blocks of the spine.

They change in shape within each part of the spine reflecting the loads they have to carry and their intricate function at each level.

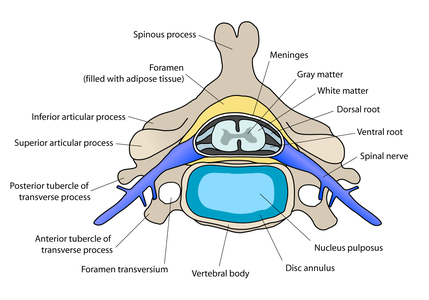

The vertebrae have multiple bony protrusions that form processes for the attachment of muscles and ligaments including the transverse processes and the spinous process at the back (the bumps that can be felt in the middle of the back).

There is a large body at the front, which joins with the vertebra above and below along with intervertebral discs sandwiched in between.

There are two bony bars that come out of the back called the pedicles that join with the lamina at the back, forming a canal inside which the spinal cord sits.

At the back, each vertebra forms two joints with the vertebra above and two joints with the one below, thereby forming a tripod like structure, with the discs at the front and facet joints at the back.

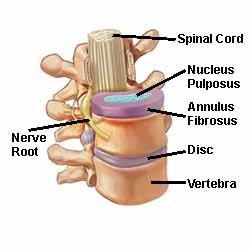

The Intervertebral Disc

The disc is sandwiched between the vertebral bodies.

It consists of a thick outer rim, similar to a rubber in a tyre called the annulus.

There is a gelatinous inner portion called the nucleus pulposis forming a donut like structure.

The disc is not a shock absorber as it is often quoted.

Its main aim is to allow the two vertebrae above and below to move in multiple planes but not to glide or shear across each other.

Disc failure is a major cause of two vertebrae ‘slipping’ over one another.

The Spinal Cord & Nerve Roots

The spinal cord extends from the brainstem at the bottom of the skull and travels down the spinal canal.

It is full of nerve cells and fibres sitting in a tube called the dural sac which is full of cerebrospinal fluid.

At each vertebra, the spinal cord gives out two nerve roots, one to each side.

At the bottom of the thoracic spine, the spinal cord thickens to form an area called the conus, at which point the cord then stops.

The remainder of the dural sac within the lumbar and sacral area is full of nerve fibres called the cauda equina as it is said to represent a horse’s tail.

The Cervical Spine

The neck consists of 7 vertebrae.

These are labelled C1 to C7. C1 and 2 have an extremely complex structure and account for nearly half of all the movement in the neck.

The neck is curved into lordosis (backwards).

There are smaller extra joins on the side called the uncovertebral joints.

C1 to C6 also have a channel to carry the vertebral artery to the brain on either side.

The nerves that exit within the cervical spine supply the hands and the breathing muscles.

The Thoracic Spine

The thoracic spine is made up of 12 vertebrae labelled T1 to T12.

The ribs are attached to all 12 vertebrae making this segment stiff, but allowing rotation.

The bones gradually get bigger as you go down, reflecting the increasing loads that each level has to carry.

The discs are frequently small in the thoracic spine that is usually curved forwards or Kyphosis.

The spinal cord is carried within the thoracic spine, giving off 12 sets of nerve roots that travel along with each rib.

The Lumbar Spine

The lumbar spine is made up of 5 large vertebrae, though in some individuals there may be 6.

The lumbar spine is curved backwards or Lordosis, which is mainly due to the height of the intervertebral discs that tend to be large, especially the L4/5 disc.

The lumbar spine is also very flexible, much like the cervical spine especially bending forwards and backwards. The nerves that exit supply the muscles in the legs.

The Sacrum

The sacrum is made up of 5 fused vertebrae making one large bone.

There are some rudimentary bones attached at the bottom called the coccyx.

The sacrum is a keystone shaping, sitting between the two iliac bones, which make up the pelvic ring.

The sacrum, like the thoracic spine is in kyphosis.

The Stable Spine

The spine is stable if it can carry out its functions so that under normal day-to-day loads it does not cause pain, deform or cause damage to the cord or the nerve roots.

This stability is maintained by the complex geometry of the bones and joint surfaces.

Under normal loads, the muscles help maintain this stable balance.

Under extremes of load, the strong ligaments take up this role.

The strength, endurance and control of these ‘core’ muscles is essential for a normal spine.

Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion (PLIF)

Definitions

Intervertebral disc – consists of a tough outer layer (annulus fibrosis (tire-like structure)) and a soft core (nucleus pulposus (gel-like substance)).

The back part of the discs are partly covered by band like ligament called the posterior longitudinal ligament.

Disc degeneration and Herniation

This usually starts in the late 30’s and 40’s.

Fissuring occurs in the annulus and the nucleus pulposus dehydrates losing the amount of gel-like material.

This presents as a black disc on a MRI scan (reported often as a degenerative disc with a disc bulge) and is very common finding in normal patients.

This in itself is not the focal cause of low back pain, though it is often incorrectly stated as being so.

However, continuing mechanical strain on the disc causes fragments of degenerate disc material to be pushed through a fissure, creating a hole in the annulus.

The disc fragment may lie beneath the longitudinal ligament, or it may burst through the ligament and lie directly under the nerve root or thecal sac (becoming a free fragment).

This fragment can cause compression of the spinal nerve roots leading to sciatica which is a cause of leg pain.

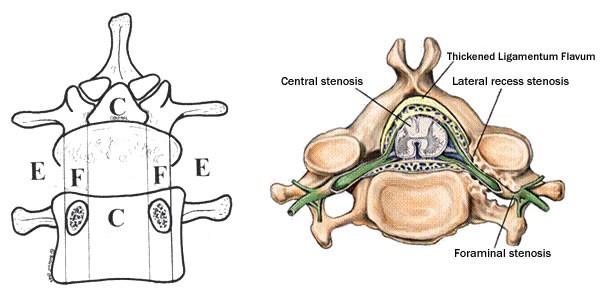

Stenosis

A common disease of the lumbar spine where a decrease in the volume of the spinal canal results in compression of the neural elements.

It may involve a narrowing of the spinal canal, the nerve root tunnel or the intervertebral foramen of a combination of these.

Absolute stenosis indicates a narrowing of 10mm or less in the AP diameter.

Relative stenosis indicates a narrowing of 10-12mm.

This may present as burning in the buttocks or legs feeling weak which comes on when you walk.

It eases when you rest or lean forward.

Primary Stenosis

Congenital / acquired – localised in posterolateral elements (the back and side parts of the spine.

A variety of conditions that's develop in later life may cause acquired stenosis such as Pagets disease of the Spine.

Congenital narrowing of the spinal canal is a result of shortened pedicles and then approximation of the posterior joints towards the midline.

This is present at birth.

Secondary Stenosis

Degenerative – due to osteophytic (bony spurs) enlargement of the inferior facets and thickening of the posteriorlateral elements.

The bulging of degenerative discs adds to the compressive element.

There are three places where the spinal nerves might be compressed, and the stenosis may be described by location.

-

Central Stenosis – in the central canal of the spinal column.

-

Foraminal Stenosis – as the nerves leave the spinal column

-

Lateral Stenosis – just after the nerve has left the canal

Spondylolisthesis – a forward shift of one vertebra upon another, due to a defect in the bone or in the joints that normally bind them together.

This can lead to stenosis occurring.

There are many causes of spondylolisthesis.

These include altered anatomy from birth (dysplastic), from degeneration (degenerative) as well as developmental (lytic).

The amount of slip can be graded:

Grade 1 <25% slippage

Grade 2 25-50% slippage

Grade 3 50-75% slippage

Grade 4 >75% slippage

Clinical Features/ Indications for surgery

Presenting Features

Central spinal stenosis

Neurogenic claudication (there is pain on walking or standing in the calves or buttocks).

Chronic sciatica on one or both sides.

Relief of pain by flexion, or upright position of lumbar vertebral column, or by sitting or lying.

Reduced SLR.

Minimal LBP.

Lateral spinal stenosis

Neurogenic claudication (but often only in one leg).

Sciatica in one leg only.

Signs of nerve root compression, pain in the leg with or without numbness, pins and needles or weakness.

Radicular symptoms.

Spinal claudication

Parasthesia (pins and needles) and heaviness.

Paresis of legs.

Partial loss of reflexes.

Investigations

Various investigations may be required including MRI scans, CT scans as well as plain x-rays.

Surgical Procedure

Surgery is performed with the patient lying in prone (face-down) on a specialist spinal surgery table.

The spine is approached through an incision in the midline of the back and the left and right lower back muscles (erector spinae) are stripped off the lamina on both sides and at multiple levels.

After the spine is approached, the lamina is removed (laminectomy) which allows visualization of the nerve roots.

The facet joints, which are directly over the nerve roots may then be undercut (trimmed) to give the nerve roots more room.

The nerve roots are then retracted to one side and the damaged disc is removed and the disc height returned to normal.

Some of the disc wall is often left to help contain the bone graft material.

The local bone that is removed is chopped into fine pieces, mixed with some blood and packed into the front of the disc.

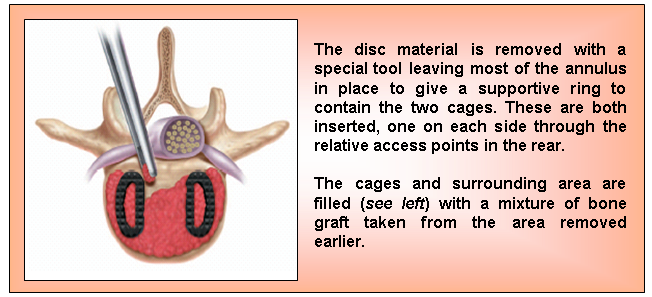

The bone is also packed into hollow rectangular ‘cages’, and these cages are inserted into the disc, one on either side.

The ‘cages’ are used to keep the 2 vertebrae apart while the bone inside the cages fuses the 2 vertebra together.

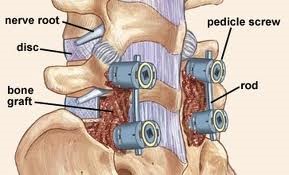

A series of screws implanted into the pedicles with rods between these screws can be used for additional support at the posterior aspect of the spine.

Post operative complications

There are several potential complications. Some of these include:

-

Dural tear - the dura is breached during the attempts to remove the disc material causing a leak of CSF.

The dura will usually be repaired using a patch, stitch or glue.

-

Haematoma - causing pressure on the nerve root / spinal cord. Presenting features will include cauda equina syndrome with motor and sensory defect with loss of reflexes.

Inform medical staff for urgent review.

-

Nerve root damage - caused by areas of swelling. Presenting features will include development of new areas of numbness, pain or weakness or worsening of existing symptoms.

Inform medical staff for review.

-

Infection – this can either be a superficial wound infection requiring antibiotics to a deep infection requiring further surgery.

-

Wound leaking

-

Non union - only determined when reviewed in clinic as the development of the bony bridge between vertebrae occurs over weeks and months.

Non-union rates are higher for patients who have had prior spine surgery, patients who smoke or are obese, patients who have had a multiple level fusion surgery, and for patients who have been treated with radiation for cancer.